Acts — Vectorized Linear Algebra Implementation

Hi everyone! Since starting this year, blogs are mandatory for all CERN-HSF contributors, I decided to take this time to make my own blog. I have written about my journey extensively there. Do give it a visit!

I have broken down the midterm project report into multiple blog posts:

The first blog post discusses what GSoC is in general, for those who might just stumble upon my blog by happenstance.

The second blog post delves into the technical details about what my project actually is, what repository I would be working with, mentions our weekly meeting schedule, and describes my three mentors.

The third blog post finishes up the trilogy by exhaustively discussing the work up till now, including benchmarking data and conclusions, and the current direction of the work.

That being said, I will also share a short report of the work I am doing, and the link to the things I have done so far below:

My progress

Fast 5×5

Benchmarking Suite for algebra-plugins

One of the main things we need, to efficiently figure out what to improve first, is a comprehensive benchmarking suite for the existing math backends. To that end, I added Google Benchmark to the algebra-plugins repository, in PR #69. Writing those benchmarks is still a work-in-progress.

Investigating Matrix Math Libraries

Then, my mentors and I spent a lot of time testing out 3 possible math backend alternatives (the custom-made fast5x5, blaze, and Fastor in a repository of mine called Fast 5×5 and comparing their performance to that of Eigen. This repository was something I forked from some prior work done on this front.

How Matrix Math Libraries Work

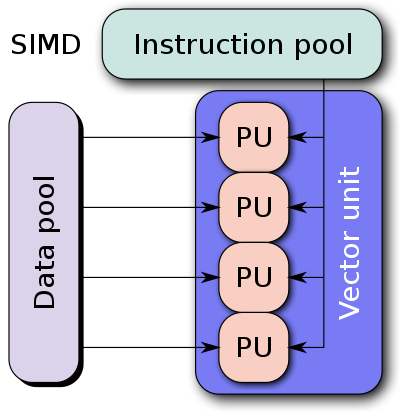

All matrix math libraries use something called SIMD (short for Single Instruction, Multiple Data) to achieve a speed-up compared to a naïve implementation.

Let’s take the example of adding two 4-dimensional vectors together. The naïve way of doing it is to take one element from each vector, add it, and then store the result in the result vector. This takes 4 add instructions to complete. However, with a SIMD ISA (Instruction Set Architecture) all one needs to do is load the 4 elements of each vector into a SIMD register, add them, and store the result in a result vector. This takes just 1 add instruction to complete.

(Picture Credits: Wikipedia, courtesy of Vadikus)

In the same vein, libraries like Eigen, blaze, Fastor, and fast5x5 use SIMD instructions to create optimized routines for tasks like matrix multiplication.

My Project

However, it was found that the performance of Eigen, which is the library that ACTS uses for matrix computations, could be improved. As a proof-of-concept, the Fast5×5 project was created to demonstrate this. The Fast5×5 library which uses xsimd under the hood for a compiler-agnostic way of exposing SIMD intrinsics.

Therefore, my GSoC project is primarily about investigating how much of a performance we stand to gain by switching matrix libraries in these projects (detray, traccc, and ACTS).

Midterm Work Summary

Once we started with the GSoC project, my mentors asked me to look at the original Fast5×5 repository and get an idea of where we stand with respect to the prior work in this project. I improved the repository in many ways, including (but not limited to)

- removing the

Dockerfileand a Bash script (among other things) in2a62718because it would not be required in this project. - revamping the project structure to make it easier for outsiders to understand where things reside. This was done multiple times (in order to keep the project structure up-to-date with the new changes), for example, in

85ad3fd,20d4fb9,125a084, and69bd4d8. - adding

xsimdandEigenas Git submodules instead of requiring the end user to have these libraries already installed in their system. This has the added advantage of allowing us to easily switch between versions ofEigenandxsimdas maintainers of those repositories continue to make bugfixes and improvements. This was done in21aad0e - updating

Eigen(first in18dbd4e, and then in0e702b0) andxsimd(ine1e1c71). The original Fast5×5 project had not been touched since 2019. In the 3 years since then, all these libraries had undergone some major version releases. - changing the benchmarking method from using

/usr/bin/timeto using Google Benchmark. Google Benchmark gives us an easy way of automating benchmarking tasks. Moreover, itsDoNotOptimize()function allows us to guarantee that the operations we are benchmarking were indeed performed and not just optimized out by the compiler. - changing the way the random matrix generation works in

ff821df. The original Fast 5×5 code used index-based operations to fill up the matrix, which is not the best way to generate reliable benchmarking data. The original code did the following for generating the matrices:

float a[SIZE * SIZE];

float b[SIZE * SIZE];

// the BaseMatrix data type in fast5x5.hpp has a constructor

// that takes in C-style arrays. So, the code simply filled

// up two arrays and then made two BaseMatrix objects out

// of them.

for (int i = 0; i < SIZE; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < SIZE; j++) {

a[i * SIZE + j] = i + j;

}

}

for (int i = 0; i < SIZE; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < SIZE; j++) {

float val;

if (i == 0 && j == 1) val = -1;

else if (i == 1 && j == 0) val = 1;

else if (i > 1 && i == j && i % 2) val = -1;

else if (i > 1 && i == j && !(i % 2)) val = 1;

else val = 0;

b[i * SIZE + j] = val;

}

}

I rewrote the matrix generation code using the random number generators in the <random> header, and mimicked Eigen’s Random() implementation, which generates a random float in the range [-1, 1]:

// random.hpp

#include <random>

#include <limits>

inline float randomFloat(float min, float max) {

// Returns a random real in [min, max].

static std::uniform_real_distribution<float> distribution(

min, std::nextafter(max,

std::numeric_limits<float>::infinity()

)

);

static std::mt19937_64 generator;

return distribution(generator);

}

// this is the matrix generation code

float a[SIZE * SIZE];

for (int i = 0; i < SIZE; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < SIZE; j++) {

a[i * SIZE + j] = randomFloat(-1.0, 1.0);

}

}

Apart from my work on Fast5×5, I also fired off a small PR which cleaned up the CI workflow files in the ACTS repository.

For the comprehensive list of changes and improvements, be sure to check out my blog post dedicated to the work I did!

Post-Midterm Work

Pre-midterm, I spent quite a bit of time writing benchmarks for testing the performance of Eigen, fast5x5, blaze, and Fastor in various matrix computation tasks like matrix multiplication, matrix inversion, computing the similarity transform and computing coordinate transforms in various matrix dimensions (more specifically, in 4×4, 6×6, 6×8, and 8×8).

I ran the benchmarks on my own machine and analyzed the performance of each backend. After a deep look into the assembly generated by each backend, as well as a look at the performance each library brought to the table, we decided to use Fastor because it was consistently first or second in all the benchmarks we threw at it, and its assembly generation was the cleanest (i.e. free of cruft and the pointless register shuffling that plagued a few of the other backends).

One of the big things I worked on post-midterm was on the visualization of the benchmarking results. We had the data, but no easy way to visualize it. I put together two Python scripts: one for generating comparative plots with all the backends together, and one to demonstrate how each backend fares alone.

Benchmark Plots

Here are the comparative plots I generated:

float matrices.

double matrices.

float matrices.

double matrices.

Note that the bar graphs for the custom backend for the 6×6 and 8×8 dimensions do not exist. This is an intentional and recurring theme: The Custom backend has a size limitation which prevents it from being usable for 6×6 and 8×8 matrices without the AVX512 instruction set, which my processor does not support. For this reason, the custom 6×6 and 8×8 data is missing from all of my benchmark plots.

float matrices.

double matrices.

float matrices.

double matrices.

float matrices.

double matrices.It is clear from these plots that Fastor is consistently near the top (i.e. either the fastest or the second-fastest in all of these tasks).

Integrating Fastor into algebra-plugins

I first had to define the math functions that live in the math subdirectory in terms of Fastor primitives and functions. After that, I had to declare the standard litany of types in the storage subdirectory. Then, I had to define the fastor_fastor frontend so that the backend is actually usable and the tests can be written.

After that, I wrote the tests. However, we ran into a small hurdle as the tests (which were written in a generic way, abstracted away from any specific backend) expect operator* to be defined for matrix-matrix and matrix-vector multiplication. However, Fastor overloads operator% for matrix-matrix and matrix-vector multiplication, and also offers the Fastor::matmul function. (It uses operator* for element-wise multiplication, instead.) This issue is yet to be resolved (at the time of writing.)

For a slightly more detailed report of what I did to integrate Fastor into algebra-plugins, check out my final GSoC blog post on my personal blog.

Concluding Remarks

This concludes my CERN-HSF 2022 GSoC blog post! It was a great learning experience for me as I got to learn a lot about SIMD and vectorization. Moreover, the opportunity to work with CERN was a great honor to me, and I also enjoyed working with mentors from different countries.

Thank you for reading!