The journey of enabling reverse-mode automatic differentiation of GPU kernels using Clad

Project: Reverse-mode automatic differentiation of GPU kernels using Clad

Mentors: Vassil Vassilev, Parth Arora

Proposal: link

Introduction

Almost a year ago, I had a university assignment on implementing the Ising model on a GPU, using CUDA. My previous experience with parallelism on a CPU, had taught me that you need to find the fine line between the benefits of workload division and the overhead of spawning threads. So you can imagine how impressed I was with the lightweight threads of CUDA. Moreover, the implementation of a scientific computing project specifically, further underlined the potential that GPUs have to offer in this field. Hence, when the Google Summer of Code projects were announced and I came across Clad and this project, it immediately captured my attention and the idea of diving into such a challenging project made me enthusiastic- and yes, this enthusiasm is still here after all these months. Though I underestimated the difficulty and the number of issues that would arise, as most participants I presume- my previous blog post is the proof of my naivety-, I believe most of the deliverables were covered and we ended up with a satisfying basic support of computing the reverse-mode autodiff of CUDA kernels. Hopefully, you, as a potential user, will agree as well.

Short background overview

Before continuing, a few things need to be addressed so we can all be on the same page.

- What’s

Clad?Cladis a clang plugin which automatically produces the derivative of a function at compile time. You can find more details inClad’s repository and documentation.

- What’s reverse-mode autodiff?

- As the name suggests, reverse-mode autodiff is the process of automatically computing the derivative of a function, but performing the operations in reverse order while also swapping the left and right hand-side expressions of these operations. This type of autodiff is used when we’re interested in the derivative with respect to many inputs of the function.

- What’s CUDA?

- CUDA is an API used to program NVIDIA GPUs.

- What’s a CUDA kernel?

- A CUDA kernel is a global void function run by CUDA on a GPU. They are launched by the host (CPU) through the syntax

kernel<<<numBlocks, numThreads, sharedMemory=0, streamId=0>>>(...). The combination of the number of blocks in the grid and threads in a block constitutes the overall number of threads that will execute this kernel. Shared memory is a virtual memory space shared by all threads in a block and its faster to access than the GPU’S global memory. Kernels are executed on a certain queue, the stream. The arguments passed to a kernel must be allocated in the GPU memory before calling them. These operations happen on the side of the host, hence the variables are stored in the global memory of the GPU.

- A CUDA kernel is a global void function run by CUDA on a GPU. They are launched by the host (CPU) through the syntax

- How can non-global device functions be accessed?

- Device (GPU) functions, with the attribute

__device__, can only be called inside kernels. They cannot be launched similarly to kernels in order to create a new grid configuration for them, rather, each thread running the kernel will execute the device function as many times as it’s called.

- Device (GPU) functions, with the attribute

Technical walk-through

1. Compilation

First step of adding a new feature in a library is successful compilation. This step took the longest to complete, as at that time I lacked some background on Clad. Specifically, Clad supports

deriving a function based on any combination of the function’s parameters. These adjoints are appended to the original function’s parameters and this is the list of the derivative function. But not quite.

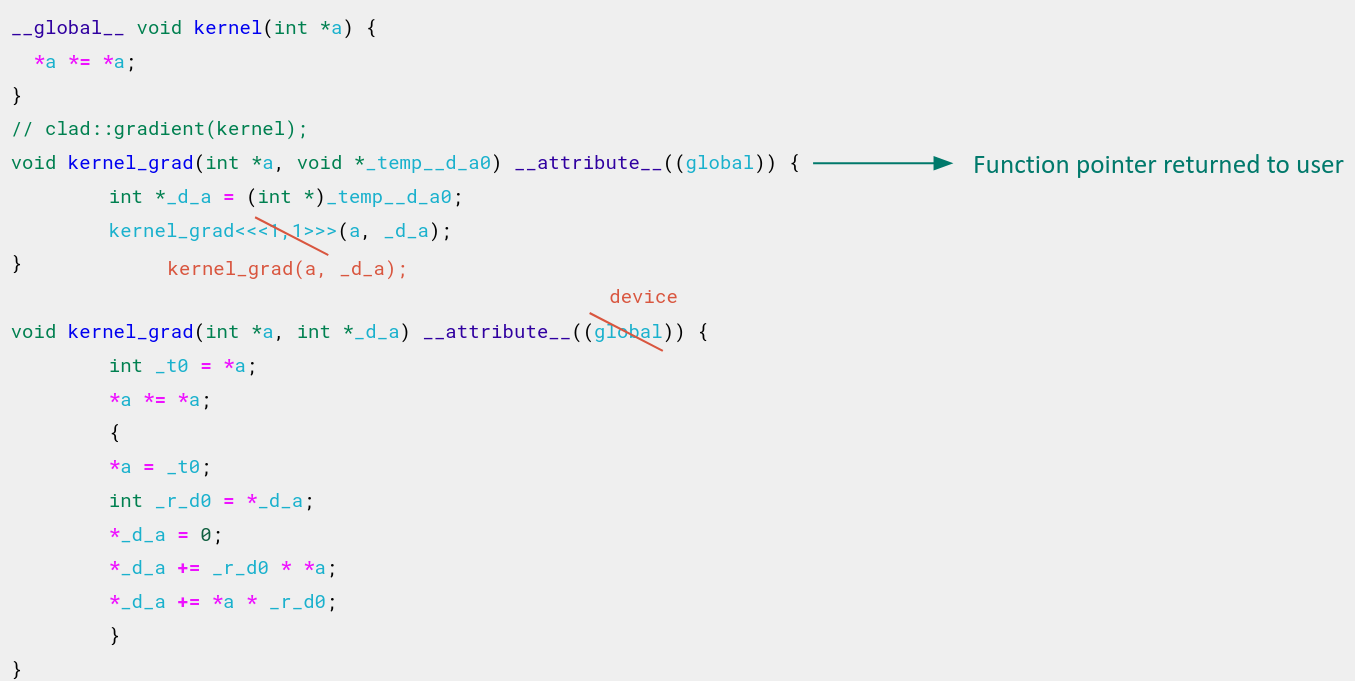

Clad traverses the code after an initial translation pass, hence, at that time the output derivative function’s signature is already formed (more on the whole process

in this introductory documentation I co-wrote with another contributor, Atell Yehor Krasnopolski). Since, we can’t tell what it should look like before actually processing the differentiation call, this signature is denoted as a void function of the original function’s parameters plus a void pointer for each one to account for their potential adjoint. This mismatch in the expected final signature and the initially created one is countered through creating a wrapper function, defined as Overload in the source code, that has the more generic, already created function signature, and contains an internal call to the produced function with the expected signature. Before this occurs, the arguments of the wrapper are typecast and mapped

to the internal function’s params. Thus, if you use the -fdump-derived-fn flag to have a look at the produced code, what you see is the internal function, but what is truly returned to you as the result to run is the wrapper function.

Coming back to the CUDA kernel case, unfortunately we cannot launch a kernel inside another kernel. That leaves us with two options:

- Transform the wrapper function into a host function, or

- Transform the internal function into a device function

Though the first option is more desirable, it would introduce the need to know the configuration of the grid for each kernel execution at compile time, and consequently, have a separate call to clad::gradient

for each configuration which, each time, creates the same function anew, diverging only on the kernel launch configuration. As a result, the second approach is the one followed.

2. Execution

Due to the fact that CUDA kernels require a grid configuration to be run and are, hence, launched differently than host or device functions, we need a new execute function,execute_kernel. From the outside, the only

difference to the already existing execute function, aside from the name of course, is that the first expects the grid configuration arguments to be provided as well, before the function’s execution args.

The capability of omitting the set of the shared memory and the stream arguments is sustained in Clad.

Option 1:

auto test = clad::gradient(F);

test.execute_kernel(grid, block, x, dx); // shared memory = 0 & stream = nullptr

Option 2:

auto test = clad::gradient(F);

cudaStream_t stream;

cudaStreamCreate(&stream);

test.execute_kernel(grid, block, shared_mem, stream, x, dx);

It is also noteworthy that execute_kernel can only be used in the case of the original function being a CUDA kernel. In similar fashion, execute cannot be used in the aforementioned case. Corresponding warnings are issued if the user mistreats these functions.

auto error_1 = clad::gradient(host_function);

error_1.execute_kernel(dim3(1), dim3(1), a, d_a); // CHECK-EXEC: Use execute() for non-global CUDA kernels

auto error_2 = clad::gradient(kernel);

error_2.execute(a, d_a); // CHECK-EXEC: Use execute_kernel() for global CUDA kernels

3. Deriving an output parameter instead of a return value

After covering the more technical aspects of the job, we are now ready to move on to what is actually being produced here.

Currently, Clad differentiates a function based on the return statement, with respect to its parameters denoted in the clad::gradient call. CUDA kernels

are void functions. You can see where I’m going with this.

Thankfully, Clad determines which statements to differentiate based on the aforementioned args of the clad::gradient call. Therefore, it suffices to include

the intended output parameter in this argument list.

__global__ void kernel(int *out, int *in);

clad::gradient(kernel, “out, in”);

4. Support of CUDA builtin variables

This break from the more complicated problems continues with the added support of the CUDA builtin variables: threadIdx, blockIdx, blockDim, gridDim, warpSize. These variables are cloned efficiently in the produced function.

5. Handling write-race conditions stemming from read operations in the original kernel

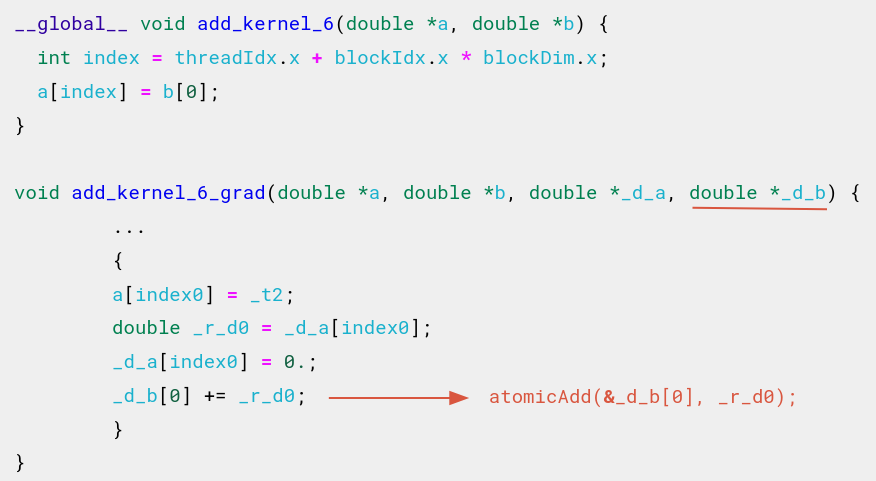

It would be too good to be true to not come across any write-race condition when dealing with parallelism.

In the reverse-mode autodiff, as previously explained, the left and right hand-side expressions are swapped. Thus, a read operation is transformed into a write operation. This becomes a problem when more than one thread reads from the same memory address and the variable stored there is of interest to the user, meaning it was part of the arg list in the clad::gradient call. In the derivative, this is translated into more than one thread attempting to write to the same memory address.

An easy way around this was the use of atomic operations every time the memory addresses of the output derivatives are to be updated.

One thing to bear in mind that will come in handy is that atomic operations can only be applied on global memory addresses, which also makes sense because all threads have access to that memory space. All kernel arguments are inherently global, so no need to second-guess this for now.

6. Deriving a kernel with nested device calls

It is usual for kernels to include internal calls to other device functions. Clad derives such functions, commonly known as pullback functions, as well as their call arguments in the original function. Doing so in the CUDA environment has to account for the inherent parallelism of the pullback function’s execution. In more detail,

if global variables are passed to the pullback function without any further action, there’s potential for write-race conditions as mentioned in the previous section. Therefore, the newly created differentiation request for the pullback function has to be aware of which parameters to treat as global variables. The global params indices are appended to the pullback function’s name to avoid reproducing the same function twice and simultaneously ensure that different combinations of global params will result in different functions being produced.

__device__ double device_fn_2(double *in, double val) {

int index = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

return in[index] + val;

}

__global__ void kernel_with_device_call_2(double *out, double *in, double val) {

int index = threadIdx.x;

out[index] = device_fn_2(in, val);

}

// clad::gradient(kernel_with_device_call_2, "out, in")

__attribute__((device)) void device_fn_2_pullback_0_1_3(double *in, double val, double _d_y, double *_d_in, double *_d_val) {

unsigned int _t1 = blockIdx.x;

unsigned int _t0 = blockDim.x;

int _d_index = 0;

int index0 = threadIdx.x + _t1 * _t0;

{

atomicAdd(&_d_in[index0], _d_y);

*_d_val += _d_y; // call arg was local to the kernel

}

}

void kernel_with_device_call_2_grad_0_1(double *out, double *in, double val, double *_d_out, double *_d_in) {

double _d_val = 0.;

int _d_index = 0;

int index0 = threadIdx.x;

double _t0 = out[index0];

out[index0] = device_fn_2(in, val);

{

out[index0] = _t0;

double _r_d0 = _d_out[index0];

_d_out[index0] = 0.;

double _r0 = 0.; // serves as _d_val in the pullback function

device_fn_2_pullback_0_1_3(in, val, _r_d0, _d_in, &_r0);

_d_val += _r0;

}

}

Nested device pullback functions follow the same pattern.

__device__ double device_fn_4(double *in, double val) {

int index = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

return in[index] + val;

}

__device__ double device_with_device_call(double *in, double val) {

return device_fn_4(in, val);

}

__global__ void kernel_with_nested_device_call(double *out, double *in, double val) {

int index = threadIdx.x;

out[index] = device_with_device_call(in, val);

}

// clad::gradient(kernel_with_nested_device_call, "out, in")

__attribute__((device)) void device_fn_4_pullback_0_1_3(double *in, double val, double _d_y, double *_d_in, double *_d_val) {

unsigned int _t1 = blockIdx.x;

unsigned int _t0 = blockDim.x;

int _d_index = 0;

int index0 = threadIdx.x + _t1 * _t0;

{

atomicAdd(&_d_in[index0], _d_y);

*_d_val += _d_y; // call arg was local to the kernel

}

}

__attribute__((device)) void device_with_device_call_pullback_0_1_3(double *in, double val, double _d_y, double *_d_in, double *_d_val) {

{

double _r0 = 0.;

device_fn_4_pullback_0_1_3(in, val, _d_y, _d_in, &_r0);

*_d_val += _r0; // call arg was local to the kernel

}

}

void kernel_with_nested_device_call_grad_0_1(double *out, double *in, double val, double *_d_out, double *_d_in) {

double _d_val = 0.;

int _d_index = 0;

int index0 = threadIdx.x;

double _t0 = out[index0];

out[index0] = device_with_device_call(in, val);

{

out[index0] = _t0;

double _r_d0 = _d_out[index0];

_d_out[index0] = 0.;

double _r0 = 0.; // serves as _d_val in the pullback functions

device_with_device_call_pullback_0_1_3(in, val, _r_d0, _d_in, &_r0);

_d_val += _r0;

}

}

7. Deriving a host function with nested CUDA calls and kernel launches

Now, what about kernels being launched inside the function to be derived instead? In a similar manner, we should ensure that any argument being passed to the kernel pullback is a global device variable.

When creating a pullback function, if all the parameters of that original function are pointers, Clad just passes the call args and adjoints to the pullback call as expected. However, if there are parameters that aren’t pointers or references, then Clad creates a local variable for each such parameter, which it passes as its adjoint to the pullback call. The returned value is added to the corresponding derivative.

This approach is true for any pullback function in Clad, but it requires extra caution in the case of a kernel pullback. Here, the local variables created for the pullback must be allocated in global device memory and properly initialized. Since these values are essential for updating the corresponding derivatives, a host variable is also required to transfer each value back to host memory, allowing it to be used in the derivative update.

int _r4 = 0;

int *_r5 = nullptr;

cudaMalloc(&_r5, 32);

cudaMemset(_r5, 0, 32);

add_kernel_4_pullback<<<1, 5>>>(out_dev, in_dev, N, _d_out_dev, _d_in_dev, _r5); // N is of type int, so r5 is passed as _d_N

cudaMemcpy(&_r4, _r5, 32, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

_d_N += r4;

cudaFree(_r5);

Kernel launches are typically preceded by calls to cudaMalloc. For this function, we need to ensure that the derivative call replicates the original allocation and that these allocations appear at the beginning of the generated code. Additionally, this derivative should be zero-initialized. This is due to the fact that any assignment in the original function corresponds to an additive update (plus-assign operation) in the derivative, in line with the chain rule.

// original code // reverse-mode derivative code (all declarations and memory allocations are placed in the beginning of this function)

double *in_dev = nullptr; --> double *in_dev = nullptr;

double *_d_in_dev = nullptr;

cudaMalloc(&in_dev, 10 * sizeof(double)); --> cudaMalloc(&_d_in_dev, 10 * sizeof(double));

cudaMemset(_d_in_dev, 0, 10 * sizeof(double));

cudaMalloc(&in_dev, 10 * sizeof(double));

For the cudaMemcpy functions, a custom built-in pullback is used to reverse the operation correctly. Specifically, the destination and source addresses are swapped and the cudaMemcpyKind value is reversed- cudaMemcpyHostToDevice is replaced with cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost, and vice-versa.

// original code // reverse-mode derivative code

kernel_call<<<1, 10>>>(out, in_dev); {

unsigned long _r2 = 0UL;

cudaMemcpyKind _r3 = static_cast<cudaMemcpyKind>(0U);

clad::custom_derivatives::cudaMemcpy_pullback(out_host, out, 10 * sizeof(double), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost, _d_out_host, _d_out, &_r2, &_r3);

} // _d_out_host data transferred to _d_out

double *out_host = (double *)malloc(10 * sizeof(double)); --> // this statement is transferred in the beginning of the produced code,

// along with its derivative

cudaMemcpy(out_host, out, 10 * sizeof(double), cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); kernel_call_pullback<<<1, 10>>>(out, in_dev, _d_out, _d_in_dev);

Finally, any call to cudaFree is moved to the end of the derivative function, along with an equivalent call for its adjoint. However, if the user has specifically requested for this adjoint, the additional call to cudaFree for the adjoint is omitted.

// original code // reverse-mode derivative code

cudaFree(a); --> cudaFree(a);

cudaFree(_d_a);

cudaFree(in); --> cudaFree(in);

Demo

And to convince you that all the above have a useful application, let’s look at the implementation of a tensor contraction gradient.

Tensor contractions are heavily used for layer dimension reduction in Machine Learning, and their gradients are crucial for optimizing network parameters. During backpropagation, tensor contractions are required to compute gradients efficiently by chaining partial derivatives across layers. This allows models to propagate errors from the output layer back through intermediate layers, updating weights in a way that minimizes the loss function. For instance, in transformer models and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), tensor contractions enable efficient handling of high-dimensional data representations while preserving essential patterns and dependencies critical to learning tasks.

With that being said, let’s look at such a code example:

typedef unsigned long long int size_type;

__device__ void computeStartStep(size_type& A_start, size_type& A_step, size_type& B_start, size_type& B_step, const int idx, const size_type A_dim[3], const size_type B_dim[3], const int contractDimA, const int contractDimB) {

size_type A_a, A_b, A_c, B_d, B_e, B_f;

switch (contractDimA) {

case 0:

A_b = idx / (A_dim[2] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 1) % 3] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 2) % 3]);

A_c = (idx / (B_dim[(contractDimB + 1) % 3] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 2) % 3])) % A_dim[2];

A_start = 0 + A_b * A_dim[2] + A_c;

A_step = A_dim[1] * A_dim[2];

break;

case 1:

A_a = idx / (A_dim[2] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 1) % 3] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 2) % 3]);

A_c = (idx / (B_dim[(contractDimB + 1) % 3] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 2) % 3])) % A_dim[2];

A_start = A_a * A_dim[1] * A_dim[2] + 0 + A_c;

A_step = A_dim[2];

break;

case 2:

A_a = idx / (A_dim[1] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 1) % 3] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 2) % 3]);

A_b = (idx / (B_dim[(contractDimB + 1) % 3] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 2) % 3])) % A_dim[1];

A_start = A_a * A_dim[1] * A_dim[2] + A_b * A_dim[2];

A_step = 1;

break;

}

switch (contractDimB) {

case 0:

B_e = (idx / B_dim[2]) % B_dim[1];

B_f = idx % B_dim[2];

B_start = 0 + B_e * B_dim[2] + B_f;

B_step = B_dim[1] * B_dim[2];

break;

case 1:

B_d = (idx / B_dim[2]) % B_dim[0];

B_f = idx % B_dim[2];

B_start = B_d * B_dim[2] * B_dim[1] + 0 + B_f;

B_step = B_dim[2];

break;

case 2:

B_d = (idx / B_dim[1]) % B_dim[0];

B_e = idx % B_dim[1];

B_start = B_d * B_dim[2] * B_dim[1] + B_e * B_dim[2];

B_step = 1;

break;

}

}

__global__ void tensorContraction3D(float* C, const float *A, const float *B, const size_type *A_dim, const size_type *B_dim, const int contractDimA, const int contractDimB) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// Each thread computes one element of the output tensor

int totalElements = A_dim[(contractDimA + 1) % 3] * A_dim[(contractDimA + 2) % 3] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 1) % 3] * B_dim[(contractDimB + 2) % 3];

if (idx < totalElements) {

size_type A_start, B_start, A_step, B_step;

size_type A_a, A_b, A_c, B_d, B_e, B_f;

computeStartStep(A_start, A_step, B_start, B_step, idx, A_dim, B_dim, contractDimA, contractDimB);

float sum = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < A_dim[contractDimA]; i++) { // A_dim[contractDimA] == B_dim[contractDimB]

sum += A[A_start + (i * A_step)] * B[B_start + (i * B_step)];

}

C[idx] = sum;

}

}

void launchTensorContraction3D(float* C, const float* A, const float* B, const size_type D1, const size_type D2, const size_type D3, const size_type D4, const size_type D5) {

float *d_A = nullptr, *d_B = nullptr, *d_C = nullptr;

const size_type A_size = D1 * D2 * D3 * sizeof(float);

const size_type B_size = D3 * D4 * D5 * sizeof(float);

const size_type C_size = D1 * D2 * D4 * D5 * sizeof(float);

// Allocate device memory and copy data from host to device

cudaMalloc(&d_A, A_size);

cudaMalloc(&d_B, B_size);

cudaMalloc(&d_C, C_size);

cudaMemcpy(d_A, A, A_size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

cudaMemcpy(d_B, B, B_size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

const size_type A_dim[3] = {D1, D2, D3};

const size_type B_dim[3] = {D3, D4, D5};

size_type *d_A_dim = nullptr, *d_B_dim = nullptr;

cudaMalloc(&d_A_dim, 3 * sizeof(size_type));

cudaMalloc(&d_B_dim, 3 * sizeof(size_type));

cudaMemcpy(d_A_dim, A_dim, 3 * sizeof(size_type), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

cudaMemcpy(d_B_dim, B_dim, 3 * sizeof(size_type), cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

// Launch the kernel

tensorContraction3D<<<1, 256>>>(d_C, d_A, d_B, d_A_dim, d_B_dim, /*contractDimA=*/2, /*contractDimB=*/0);

// Copy the result from device to host

cudaMemcpy(C, d_C, C_size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

// Free device memory

cudaFree(d_A);

cudaFree(d_B);

cudaFree(d_C);

cudaFree(d_A_dim);

cudaFree(d_B_dim);

}

To execute this, the user should provide the necessary arguments of launchTensorContraction3D and retrieve the result. What if we also needed the gradient as well?

You might be surprised to learn that initializing the derivatives of interest is all that’s needed! That’s right—there’s no requirement for additional GPU memory allocations, assignments, or deallocations from your side. You won’t need to create any extra parameters beyond those requested, nor will you have to break down the gradient call into multiple ones. To add to that, you can execute both the original and the derivative function with a single call to the execute function of the CladFunction object.

int main() {

const size_type D1 = 2, D2 = 3, D3 = 4, D4 = 3, D5 = 2;

float A[D1][D2][D3] = {

{ {1, 2, 3, 4}, {5, 6, 7, 8}, {9, 10, 11, 12} },

{ {13, 14, 15, 16}, {17, 18, 19, 20}, {21, 22, 23, 24} }

};

float B[D3][D4][D5] = {

{ {1, 2}, {3, 4}, {5, 6} },

{ {7, 8}, {9, 10}, {11, 12} },

{ {13, 14}, {15, 16}, {17, 18} },

{ {19, 20}, {21, 22}, {23, 24} }

};

float C[D1][D2][D4][D5] = {0}; // Result tensor

// Compute the gradient

auto tensor_grad = clad::gradient(launchTensorContraction3D, "C, A, B");

// Initialize the gradient inputs

float gradC[D1][D2][D4][D5] = {

{

{ {1, 1}, {1, 1}, {1, 1} },

{ {1, 1}, {1, 1}, {1, 1} },

{ {1, 1}, {1, 1}, {1, 1} }

},

{

{ {1, 1}, {1, 1}, {1, 1} },

{ {1, 1}, {1, 1}, {1, 1} },

{ {1, 1}, {1, 1}, {1, 1} }

}

};

float gradA[D1][D2][D3] = {0};

float gradB[D3][D4][D5] = {0};

// Execute tensor contraction and its gradient

tensor_grad.execute(&C[0][0][0][0], &A[0][0][0], &B[0][0][0], D1, D2, D3, D4, D5, &gradC[0][0][0][0], &gradA[0][0][0], &gradB[0][0][0]);

// Print the result

std::cout << "Result C:\n";

for (int i = 0; i < D1; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < D2; ++j) {

for (int k = 0; k < D4; ++k) {

for (int l = 0; l < D5; ++l) {

std::cout << C[i][j][k][l] << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

std::cout << "Result C_grad w.r.t. A:\n";

for (int i = 0; i < D1; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < D2; ++j) {

for (int k = 0; k < D3; ++k) {

std::cout << gradA[i][j][k] << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

std::cout << "Result C_grad w.r.t. B:\n";

for (int i = 0; i < D3; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < D4; ++j) {

for (int k = 0; k < D5; ++k) {

std::cout << gradB[i][j][k] << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

return 0;

}

Now that’s easy. And, thus, cool.

Future work

One could claim that this is the beginning of a never-ending story. There are numerous features of CUDA that could be supported in Clad, some of them being:

- Shared memory: Shared memory can only be declared inside a kernel. Since,

Cladtransforms the original kernel into a device function, no declaration of shared memory can be present there. There are ongoing discussions on the need of the overload functions and the produced function’s signature. - Synchronization functions, like

__syncthreads()andcudaDeviceSynchronize() - Other CUDA host functions

- CUDA math functions

It is also very interesting, and probably necessary, to explore the performance of an analysis on the produced CUDA kernel in order to minimize their memory footprint and execution time.

Final remarks

Though there’s still work to be done, I’m very proud of the final result. I would like to express my appreciation to my mentors, Vassil and Parth, who were always present and whose commentary really boosted my learning curve. Through this experience, I gained so much knowledge on CUDA, Clang, LLVM, autodiff and on working on a big project among other respectful and motivated people. It certainly gave me a sense of confidence and helped me get in touch with many interesting people, whom I wish I had spared more time off work to get to know better. Overall, I really treasure this experience, on both a technical and a personal level, and I’m very grateful for this opportunity!