Neural (De)compression for High Energy Physics

| Name | Yolanne Lee |

| Organisation | CERN ATLAS Project, Argonne National Laboratory |

| Mentor | Dr. Maciej Szymański, Dr. Peter Van Gemmeren |

| Project | Neural (De)compression for High Energy Physics |

Introduction

In high-energy physics experiments such as those at CERN’s ATLAS project, immense volumes of data are generated. This project explores the feasibility for “precision upsampling” using deep generative models to be used to reconstruct high-precision floating-point data from aggressively compressed representations. I had the opportunity to work on this topic under the support and supervision of Maciej Szymański and Peter Van Gemmeren, with the ATLAS Software & Computing group at CERN and Argonne National Laboratory.

Two more streamlined data formats are being developed and refined for the ATLAS project: The DAOD_PHYS and DAOD_PHYSLITE, requiring approximately 50kB/event and 10kB/event respectively. While lossless compression is already employed to manage this data, lossy compression (specifically of floating-point precision) offers more aggressive reductions, potentially decreasing file sizes by over 30%. This is in part limited by the presence of other data types present in the DAOD files. However, this comes at the cost of irreversibly discarding information, raising the challenge of how to recover or approximate full-precision data for downstream analysis.

Contents of a DAOD_PHYSLITE file

| Data Type | % Branches Comp | % Branches Orig | % Size Comp | % Size Orig | Count Comp | Count Orig | Size (MB) Comp | Size (MB) Orig | |------------------|-----------------|-----------------|-------------|-------------|------------|------------|----------------|----------------| | AsDtype | 3.15 | 3.15 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 0.22 | 0.24 | | float32 (>f4) | 34.92 | 34.92 | 57.96 | 67.88 | 276.50 | 276.50 | 91.53 | 147.30 | | group | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | | int32 (>i4) | 2.22 | 2.22 | 2.94 | 2.20 | 17.50 | 17.50 | 4.73 | 4.81 | | int64 (>i8) | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 | | jagged_array | 13.72 | 13.72 | 8.50 | 6.41 | 108.50 | 108.50 | 13.32 | 13.66 | | object_container | 21.00 | 21.13 | 15.96 | 12.74 | 218.50 | 219.50 | 30.72 | 32.95 | | strided_object | 12.93 | 12.93 | 6.22 | 4.69 | 133.00 | 133.00 | 13.37 | 13.44 | | uint32 (>u4) | 10.66 | 10.54 | 7.68 | 5.52 | 84.50 | 83.50 | 12.27 | 11.90 | | uint64 (>u8) | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 0.90 | 0.90 | | unreadable_branch| 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |This project proposes a novel approach using deep probabilistic models to reconstruct high-precision floating-point data from aggressively compressed representations, a problem coined here as precision upsampling. The goal is to explore and compare the capabilities of three classes of generative models: autoencoders, diffusion models, and normalising flows. Each model type offers distinct advantages: autoencoders are well-studied in neural compression, diffusion models are robust to noise and excel in reconstructing multi-scale structures, and normalising flows offer exact likelihood estimation and invertible mappings that align well with the structured nature of physical data.

Context

In preparation for the High-Luminosity Large Hadron Collider project, two more streamlined data formats are being developed and refined for the ATLAS project: The DAOD_PHYS and DAOD_PHYSLITE, requiring approximately 50kB/event and 10kB/event respectively. Data compression is essential in high energy physics due to the scale of data being generated, and storage and access to this data becomes infeasible without compression; upgrading hardware and developing more advanced storage technology is not only expensive but also tends to lag behind developments in software, and as such, a variety of classical and neural compression techniques have been introduced in the physics domain.

Currently, the implemented lossy compression reduces the precision of a 32-bit IEEE 754 floating-point number by truncating its mantissa to a specified number of bits while applying rounding to the nearest representable value.

A 32-bit IEEE 754 float consists of:

bits = [ s | eeeeeeee | mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm ]

^ ^^^^^^^^ ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

1 bit 8 bits 23 bits

where:

- $s$ is the sign bit,

- $e$ is the exponent in biased form ($e \in [0, 255]$),

- $m$ is the mantissa (fraction) with an implicit leading 1 for normalised values.

The lossy compression currently implemented in ATLAS operates by breaking a float number into its sign, exponent, and mantissa bits. The mantissa is then rounded to the nearest representable value by adding a rounding bit and truncating the lowest $k$ bits. Finally, the number is reconstructed using the same sign and exponent but with the shortened mantissa, producing a lower-precision approximation of the original.

| Type | Avg Original Size (MB) | Avg Compressed Size (MB) | Compression % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real Data | 225.27 | 167.10 | 25.82% |

| Simulated Data | 742.51 | 539.38 | 27.36% |

When truncating the last 10 mantissa bits, the compression observed is non-negligible and at scale represents a significant reduction in file storage sizes. However, the bits once lost are lost forever and this represents an ill-posed problem where we lack sufficient knowledge to retrieve any of the lost information.

Theoretical Framework and Proposed Method

My project took a short journey through the impact that mantissa truncation has on the resulting data. What exactly does it mean to truncate $n$ bits, realised in base-10 representation?

Github Repository: See the journey from analysis to exploratory approaches here!

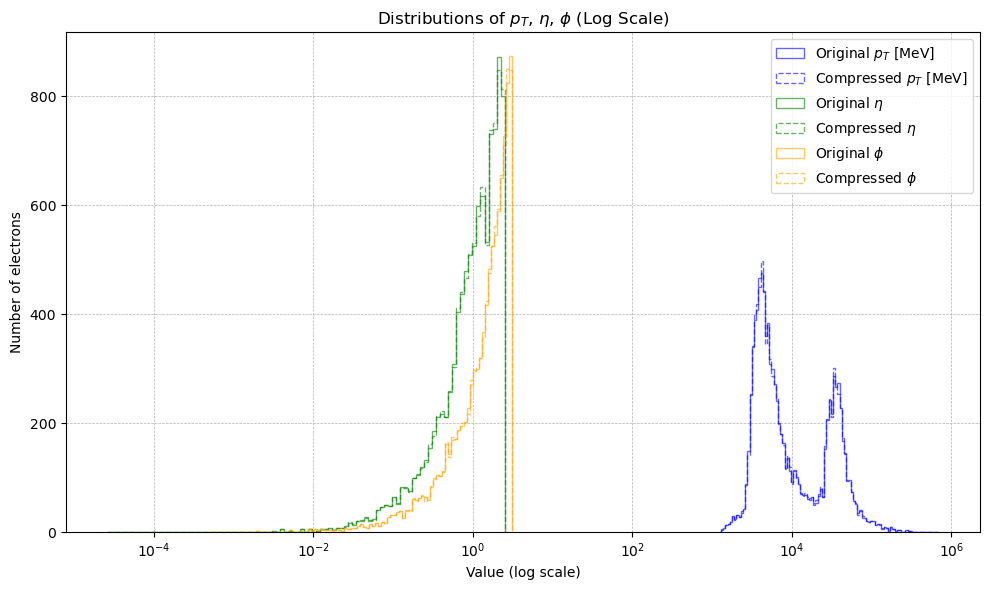

I visualised the original and lossy-compressed data, focusing largely on the momentum, eta, and phi values of electrons within the PHYSLITE files. These recorded the motion and direction of the electrons, where $\vec{p}$ (momentum) tells how fast they are moving, η (eta) describes the angle at which they travel relative to the main particle beams, and φ (phi) gives the direction around those beams.

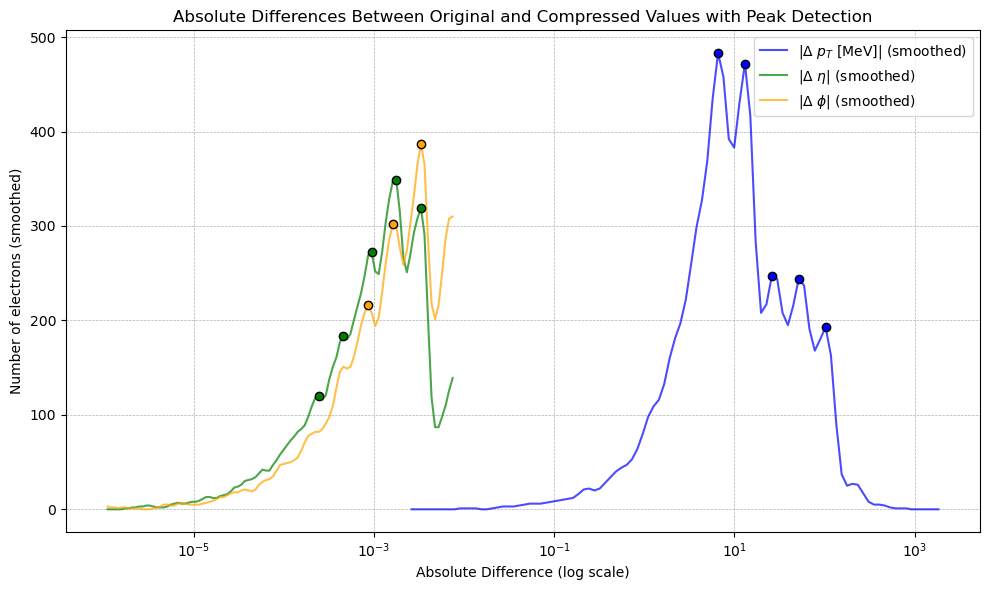

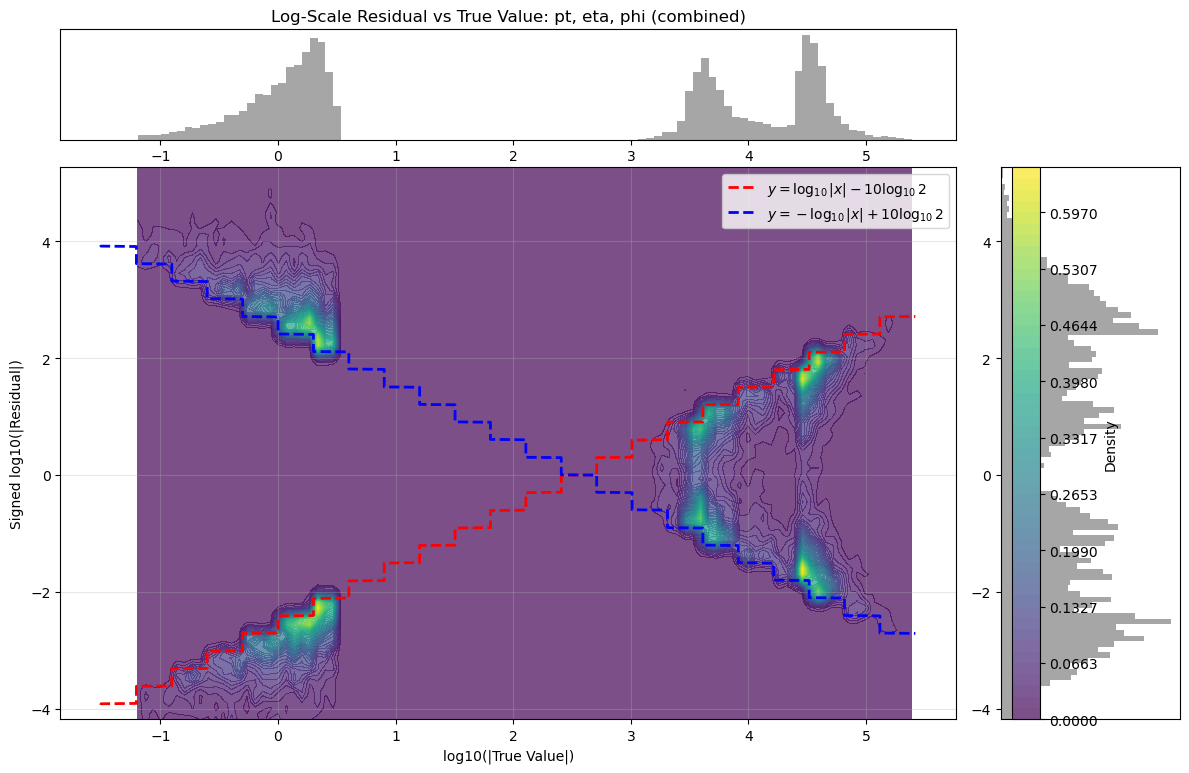

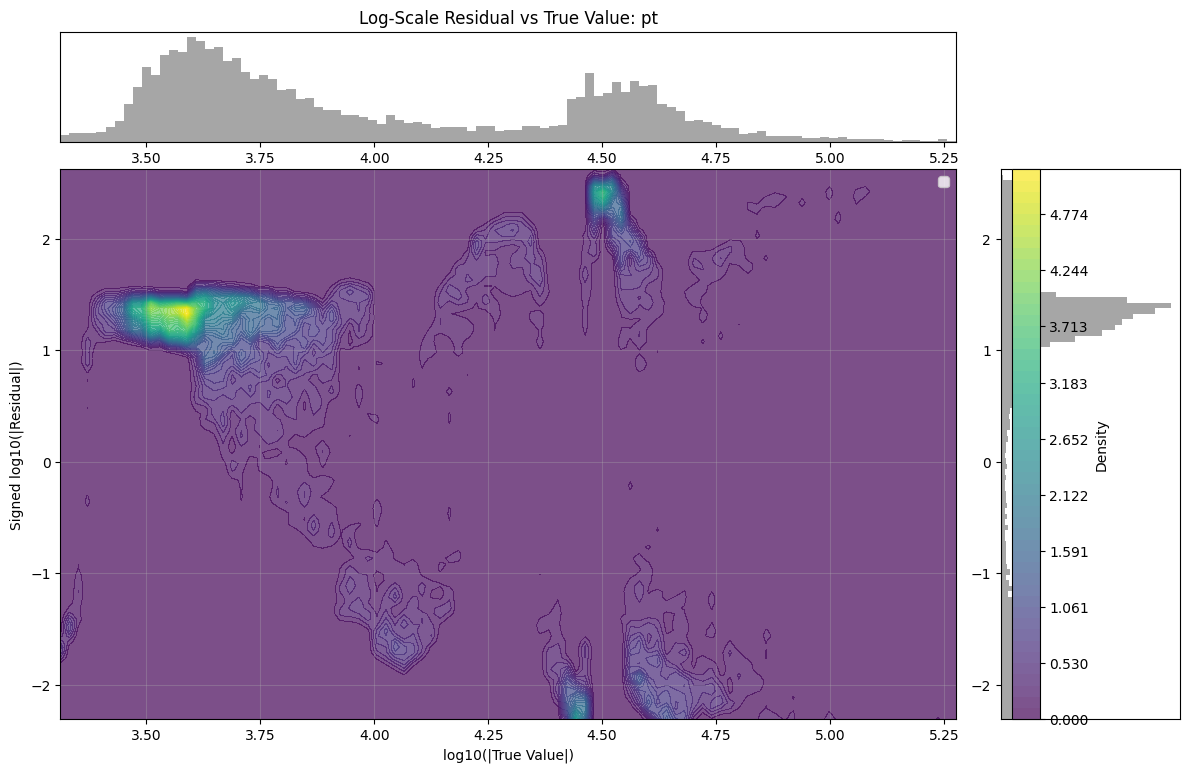

An interesting phenomenon occurs when observing the data plotted on a log-scaled $x$-axis. To further investigate, we plotted this with some light Gaussian smoothing. The resulting peaks appeared to have some regular spacing (specifically, $\Delta \log_{10} \approx 0.28 \;\Rightarrow\; \text{ratio} \approx 1.9$). In fact, investigating the residuals in the same log $x$ scaling resulted in distinct patterns.

This represented the core theoretical output of the project. We found such regular, stepped patterns in the residual in all truncated float data which we understood was likely some generalised quantisation error that occurs due to discarding $n$ bits. The next step was then to rigorously derive the actual mechanism by which the residual changes based on the truncation amount. This theoretical model had not been found in literature in specifics, so this was a particularly exciting outcome. The full derivation can be found here, with the model as follows:

- Final symmetric bounds:

| <img src=”https://raw.githubusercontent.com/yolannel/ATLAS_decompression/refs/heads/master/figures/expression.png” alt=”log10 | Δ | _signed ∈ [ -log10 | x | + m·log10(2), log10 | x | - m·log10(2) ]” width=60%> |

- These bounds form two diagonal lines on a log–log plot of

log10|x|vs.log10|Δ|. - Slopes: ±1

- Vertical intercepts: determined by

m * log10(2) - The step-like function seen in real-valued data has step sizes of approximately

Δ log10 ≈ 0.28 ⇒ ratio ≈ 1.9, as in the peak spacing before.

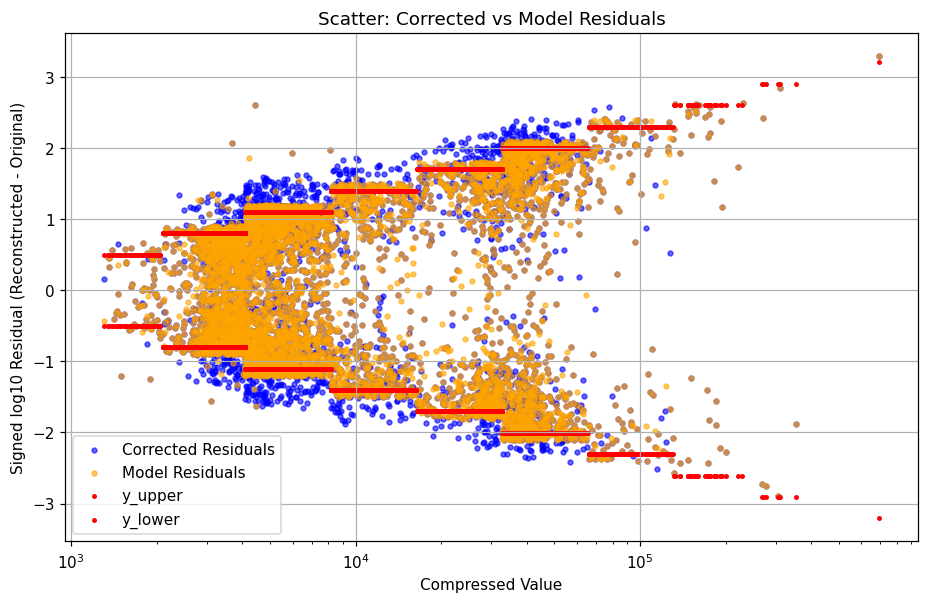

As a result, the project diverged slightly to explore how we can appropriately leverage this theoretical model to target any reconstruction of the remaining bits to quantisation error, rather than a blanket recovery.

<img src=”https://raw.githubusercontent.com/yolannel/ATLAS_decompression/refs/heads/master/figures/system_diagram.png” alt=”System diagram of proposed neural decompression model.” width=60%>

The current work in progress attempts to use the previously defined probabilistic models to model the distribution of data in varying ways, for which the residual can then be calculated and compared to the theoretical maximum and minimum bounds to determine how likely the residuals are to be due to quantisation. This hybrid approach is designed to minimize ‘hallucinations’ in the precision upsampling pipeline which could discard or modify important anomalies which can occur and are of particular interest in HEP data.

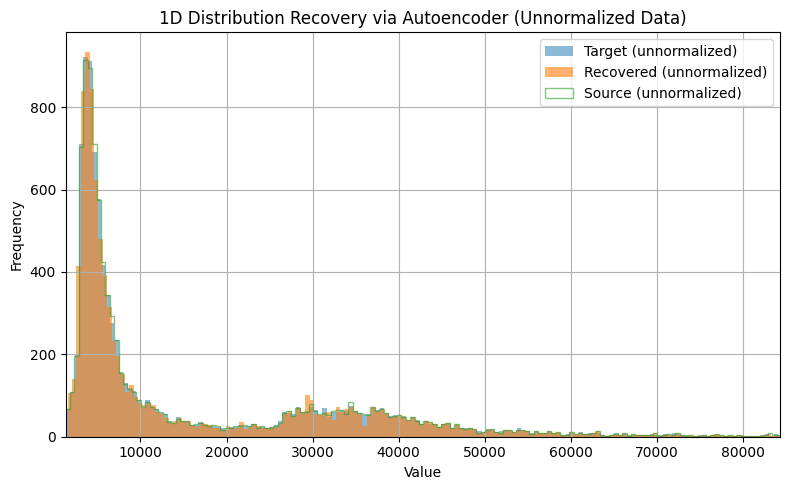

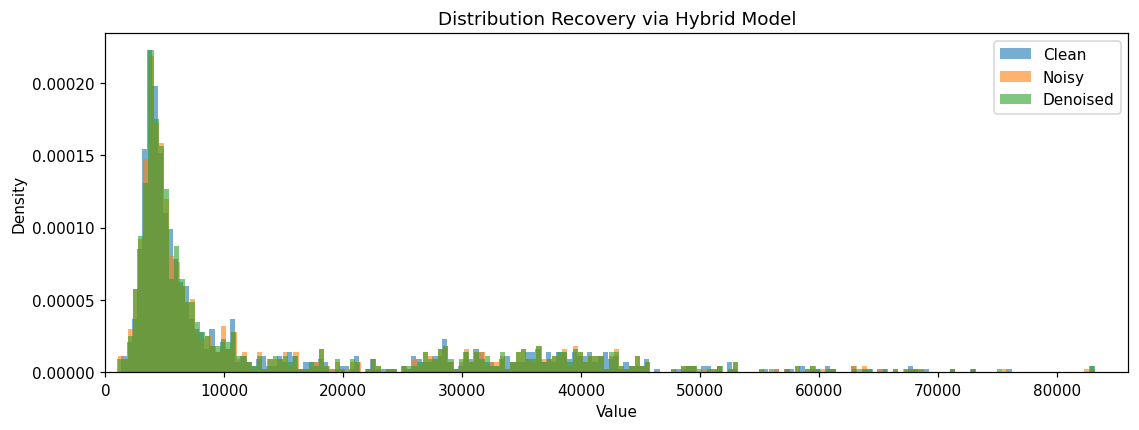

As a part of exploratory work, I have implemented autoencoders, variational autoencoders, and flow matching models to successfully reconstruct the distributions of the data of interest (currently, the momentum, eta, and phi of electrons as a minimal test set), demonstrating that such models are sufficiently complex to capture the characteristics of the data. These models also carry additional benefits such as retrievable statistical characteristics and densities, which could benefit downstream usage.

In the context of the proposed pipeline, I had first attempted to train an autoencoder (taking the simplest model to create a ‘minimum viable product’, as it were) under a denoising workflow wherein I have as input to the model the compressed data, optionally with some added noise. The output of the model, then, is trained to be the ‘denoised’ data (where if no noise was added, one can consider the mantissa truncation to add ‘quantisation noise’) and MSE loss is taken of the model output versus the original, uncompressed data. The addition of some small amount of Gaussian noise is a common technique which I use in my day-to-day work and can often encourage the model to learn more effectively. Models at this scale are easily and quickly trained on an NVIDIA RTX4080, with 100 epochs taking on average ~15 minutes, or during testing, converging sufficiently within 30 epochs to establish a rough performance measure. All models were implemented using pytorch, with additional functionalities used for evaluation using scikit-learn statistics and numpy operations where necessary. All models were implemented using pytorch, with additional functionalities used for evaluation using scikit-learn statistics and numpy operations where necessary.

| Method | Comparison | log-MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Autoencoder | Compressed → Source | 2.75e-06 |

| Corrected → Source | 2.18e+00 |

In fact, however, this naive correction results in a significantly worse match to the source data: the original lossy compression is more accurate to the uncompressed data than the autoencoder outputted estimate. Another approach under development is to treat the data as an inpainting problem, commonly seen within image generation where some part of an image may be blacked out; an inpainting model is designed to ‘fill in the blanks’. In our case, we not only have the new theoretical bounds but also the first $23-n$ bits of data that is retained after truncation: this is valuable information which, in statistical tests, is also often a ‘good-enough’ approximation of the uncompressed data to begin with. Then, the challenge is only to ‘fill in’ the remaining truncated $n$ bits which represents an even more bounded problem space and would minimise unexpected upsampling artifacts by constraining any correction terms to be within the allowable $n$ bits of change.

| Method | Comparison | log-MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Hybrid | Compressed → Source | 2.72e-06 |

| Corrected → Source | 4.60e-06 |

This hybrid model performs significantly better than the autoencoder approach; however, it is still less accurate than the actual compressed data. While this project has not yet conclusively found a candidate model to precision upsample, ongoing work is being performed toward proposing a working pipeline based off of the work performed up to this point. In short, autoencoders, variational autoencoders, and some simple flow matching models have been implemented and tested, with performance measured using simple MSE loss as well as distribution-based metrics such as KL divergence. In the GitHub repository, a series of notebooks show how data was initially explored, then through the process of discovering, verifying, and ablating the theoretical bounds for lossy mantissa truncation compression, and finally do the initial work of designing an appropriate ‘neural de-compression’ system.

My thoughts on GSoC

I had first approached my mentors and this project with the excitement of applying some of my current research in generative models for scientific machine learning directly to this precision upsampling problem, drawing parallels between ‘making the numbers more precise’ and ‘superresolving medical images’, for example. However, despite the extensive data exploration we performed and the theoretical work I ended up doing stalling the work directly applying deep learning models to these PHYSLITE file data, I found it both satisfying in being able to derive a clear reason to the phenomena I observe in the data but also extremely informative in terms of designing (as a work in progress) a more rigorous deep learning system. I have also had the opportunity to present my work to the ANL Software & Computing group and during the ATLAS S&C Week workshop, which generated some useful discussion which I look forward to applying to my work.

Working on HEP data was both fascinating from the subject matter but also in terms of the problem area being tackled, and I hope that my continued work can benefit not only this specific upsampling target for PHYSLITE data, but lossy compression as a whole. My time working with my mentors was fruitful and inspiring, and I felt integrated into the group via group meetings and the strong support that both mentors provided throughout the project. I am thankful for such an exciting opportunity as well as my mentors’ insightful feedback each week, and I look forward to continuing my work beyond this summer with them!